The Artistic Legacy of Painting: Insights from the Markandeya Purana

Painting like any other artistic achievement is the result of a world wide web. Each society inherits its own artistic inclinations, which are influenced by various manifestations of art from the world over. The Markandeya Puranam says "Painting is of four kinds: (1) 'true' to life (satya), (2) 'flute player' (vainika), (3) 'of the city', or 'common man' (nagara), and (4) 'mixed (misra). When the painting bears a resemblance to this earth with proper proportion, tall with a nice body, round and beautiful, it is called 'satya'. 'Vainika', is rich in the display of postures, maintaining exact proportions, placed in an exactly square field, not phlegmatic, not very long but well finished. The paintings known as 'nagara', are round, with firm and well-developed limbs, with scanty garlands and ornaments. Oh! best of men, the 'misra' derived its name from being composed of the former three categories".

"Methods of producing light and shade are said to be three: (1) crossing lines in the form of leaves (patraja) (2) by stumping (airika) and (3) by dots (binduja). The first method of shading is called 'patraja' on account of lines in the shape of leaves. The 'airika' method is so called because it is said to be very neat and fine. The 'binduja' method is so called from the restrained (i.e. not flowing) handling of the brush".

"Indistinct, uneven and inarticulate delineation, representation of human figures with lips too thick, eyes and testicles too big, and unrestrained in movements and actions;

such are the defects of chitra (pictorial art). Sweetness, variety,spaciousness of background (bhulamba), proportionate to the position of the figure (sthaana), similarity to what is seen in nature and minute execution are mentioned to be the good qualities of chitra. In works of chitra, delineation, shading, ornamentation and colouring should be described as decorative (i.e. the elements of visualization). The masters praise the rekhas (delineation and articulation of forms), the connoisseurs praise the display of light and shade, women like the display of ornaments, and the rest of the public like richness of colours. Considering this, great care should be taken in the work of chitra so that, it could be appreciated by every one. Bad seat, thirst, inattentiveness, bad conduct and behaviour are the root evils (in the painter) that destroy his painting. In a work of painting, the ground should be well chosen, well covered, very delightful, pleasant in every direction, and its surface (lit. space) should be well coated (lit. anointed). A painting will be then very beautiful, when a learned artist paints it with golden colour, with articulate and yet very soft lines, with distinct and well arranged garments, and lastly not devoid of the beauty of proportionate measurement".

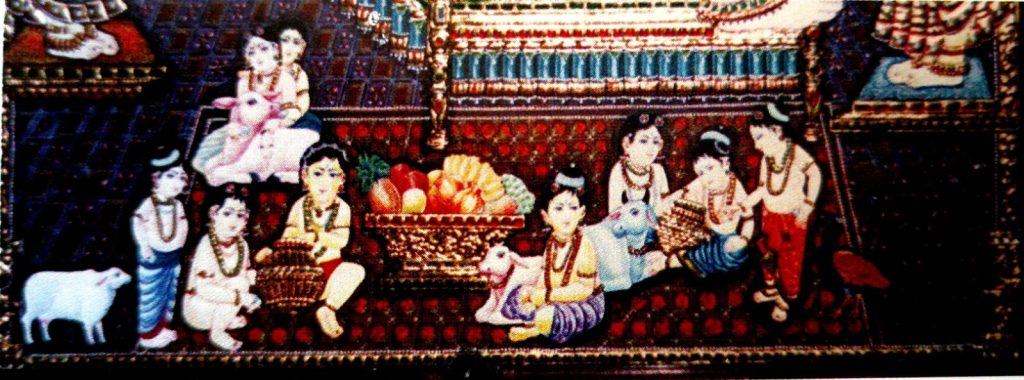

As we look at the development of Indian paintings through the centuries on the basis of the above description from Markandeya Purana we see different styles and schools emerge often very distinctive. One remarkable phase in the traditional development of painting is the Tanjore school of painting developed in South India in 18th and 19th century.

The Evolution and Cultural Significance of Tanjore Painting

The Tanjore style of painting is not basically an indigenous painting tracing to the earlier Chola period.It is a part of the larger Karnataka style of painting that descended down from the Vijayanagarempire. The Vijayanagar empire was disintegrated at the battle of Talikota. In those days the art was highly functional. Specific occasions demanded demonstrations of art. Thus art became part of the pattern of life. The onset of the spring season needed Vasantha mandapam in the temples, 'Greeshma', the summer season needed choultries for taking rest, the 'Varsha' and the 'Sharat rithus' (seasons) needed caves and viharas for chaturmasyas and the 'Hemanta' and 'Shisira rithus' needed magnificent courts and durbars. The Vishnu Dharmottaram said that the general class of poor people usually built their residences with their own hands and only the kings and aristocrats could afford to have artistic buildings. Art was thus unconsciously bifurcated into two traditions, the great tradition which also included literature; public buildings which were limited to Hayagrival temples, mandapams, chatrams and viharas; the little tradition were folk arts, music, artefacts, building small residences etc. When the Nayak dynasty was ruling Thanjavur, its rulers brought with them certain Vijayanagar artists and also their traditions of paintings and sculptures. These traditions were bound by the earlier Vedic traditions of shilpa nirman and chitra nirman.

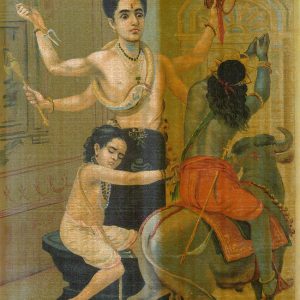

Lord Ganesha, Lord Chaturmukha Brahma, Lord Shiva giving refuge to Markandeya, the shastrartha (intellectual discourse) between Adi Shankara and Mandanmisra or between the atheist and the theist as in Prabodhachandrodaya, the Hayagriva surrounded by apsaras and being carried on a palanquin, the Goloka and the Kamadhenu concepts, the praja waiting for audience at

the durbar, Aswa pradarshana, the 48 presentations of Sri Krishna leela, Rama, Lakshmana, Sita and Guha at Chitrakuta, the coronation of Rama, the guru-shishya parampara and Dakshinamurthy representation, Ahalya shapavimochanam, Dhanur bhangam, Tataka maaranam, Narada pravesham, Mohini Bhasmasura prasanga, Shiva bhikshatanam, Sravana shaapanam, Indra shaapanam, Muchukunda prakaranam, Nataraja nrityam, Skanda viharam, Ratimanmatha kalapam, Sagara putra shaapavimochanam, Gangavatharanam, 108 incidents of Mahabharatam, Parvati parinayam, Kumarasambhavam, Rajaveethigamanam, Sahasra sheersha purusha darshanam were all presented in paintings.

In this way about 1008 subjects were chosen as slaghya (acceptable) for pictorial representation in murals and paintings. Amongst animals and birds the following were permitted to be represented.